Somewhere In the Middle of Rotuma

It warmed all the way up to -4 on the December day I spoke with Kathy Weber-Bates about the South Pacific island of Rotuma, each of us thinking it sounded pretty inviting right about now. For me, Rotuma also sounds the way lots of people who’ve never been to Montana talk about it: it’s far away and word is, it’s very beautiful. For Kathy, who was born and raised in Montana and who’d never been to Rotuma until March of this year, the island is, in profound ways, simply home.

Born in a garage in Stevensville—more on that in a bit—to American Peace Corps volunteer Jerry Weber and Rotuman Lusie Samuela, Kathy grew up in Montana but with the culture and viewpoint of her ancestral homeland always in the background. Her mother sang songs to Kathy and her siblings in Rotuman and taught them to see the world through Rotuman eyes, but chose to raise her kids as Americans to prioritize their education and future success. The tenuous threads of Rotuman language, geography and family ties can all become endangered in a cultural diaspora, but for Kathy preserving and participating in her family’s history began with a well-timed—and very long-distance—phone call.

Rotuma Project cofounders Kathy Weber-Bates and Jonathan Fong.

Kathy’s cousin Jonathan Fong, a prominent Rotuman videographer living and working in Fiji, contacted her to ask if she’d be interested in partnering with him in an effort to document Rotuman culture through moving images. The two had led oddly parallel lives growing up, both choosing to work in film and graphic design with a love for storytelling—skills ideal for preserving and honoring the place they’d come from. And though Jonathan lived “only” 350 miles from Rotuma, he’d never been there either. For Kathy, whose communications firm works with nonprofits and others, her skills and interests were ideally suited to documenting the landscape and people of her homeland. As a seasoned journalist who has taught video storytelling at the University of Montana School of Journalism, Kathy was inspired by the idea of using her professional skills to somehow contribute to her island home. “That sounds fascinating,” she thought at the time, “especially for Rotuman descendants who can’t get back to Rotuma.”

It was compelling for personal reasons, too. Her brother unexpectedly passed away from cancer in 2020, as had her mother in 2017. At the end of her life, Kathy’s mother, Lusie, wished to be surrounded by large photos of Rotuma and the sounds of its music, which were perhaps more comforting than the pain medications she was receiving. Kathy now knew she had to go to Rotuma not just for herself, but for her family as well, and help create what would become The Rotuma Project. “It wasn’t just a bucket list item,” she remarks. “I was on a mission.” So she and Jonathan began planning their first trip. But getting there was no casual undertaking.

To call Rotuma remote is an understatement. The island lies 1,500 miles north of New Zealand and 2,000 miles east of Australia. Put another way, if you could charter a direct flight from Kathy’s home in Missoula, after six hours and 3,000 miles you’d be over the Big Island of Hawaii—and only halfway to Rotuma. Typically, visitors fly to Fiji and then hop a shorter flight north to Rotuma itself.

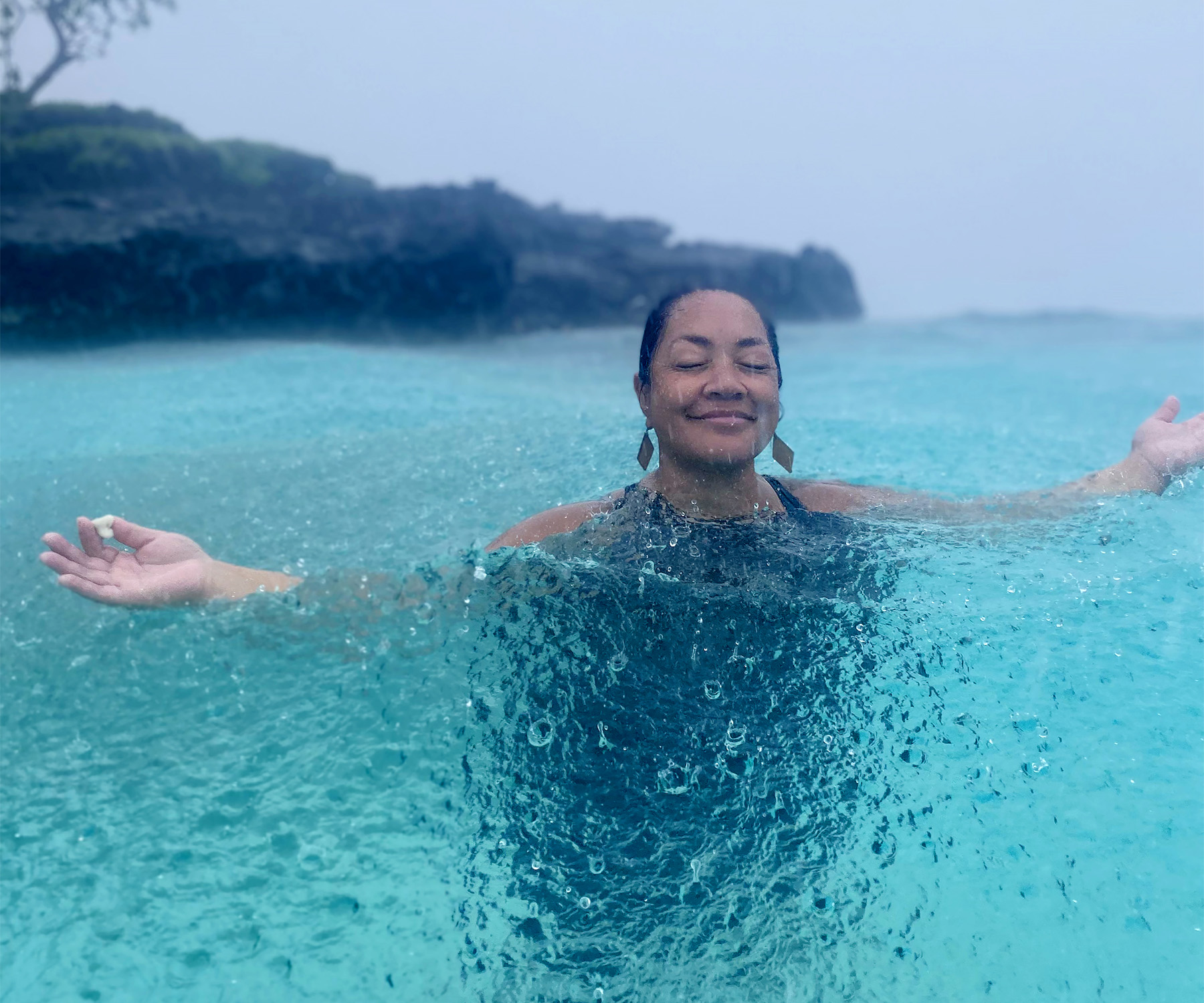

But no amount of distance would’ve kept Kathy from going. “It’s a responsibility that I know I have.” Once there, she and Jonathan met and stayed with family members and began touring the island. Only 9 miles wide and 2 miles tall (about the size of Billings), it doesn’t take long to visit every corner of Rotuma. But each had significance for Kathy; she was able to see where her mother was born and lived, and every stop was an education on the Rotuman way of life. The island is only partially electrified; many people often share generators to recharge cell phones, and refrigerators are rare. “On the flip side of that,” Kathy notes, “Everything we ate was organic and fresh.” The land and sea provide much of the residents’ diet, just as they have for generations, and Rotumans’ connection to place runs very deep.

It’s a connection threatened not just by people leaving Rotuma for better opportunities, but by the Pacific’s changing weather. Kathy talks about how Rotuma is experiencing storms of increasing intensity which are altering its coastlines, none of which the small island can afford to lose. “For our people and our culture, every story, every family, every dance, every chant is connected to the land. So to say that your homeland will no longer be around due to climate change is an existential threat to culture.” Even Rotuma’s distinct language is threatened, which is why Kathy’s now learning to speak it as she and Jonathan document its use. “The UN designated the Rotuman language one of the most endangered Indigenous languages on Earth, and that’s my mother tongue.”

Watching a place you love undergo change is something that’s become a familiar refrain here in Montana, too. I asked Kathy what Rotumans living in the middle of the Pacific might have in common with people living here in the heart of North America. She immediately touched on a shared love of the land. “Montanans, we’re outdoor people; we feel good when we’re spending time outside.” She noted that her parents had found a particularly obvious connection between life in Rotuma and in Montana. “One of their favorite things to do was going fishing together at Georgetown Lake. My mother was an excellent fisherwoman, and that came from growing up fishing with her dad in Rotuma.”

Kathy noted another kinship Montanans have with the people of the island. “We’re neighborly and Rotuma is rural, and neighbors help neighbors.” The kind of mutual support found in rural communities seems to be universal, and she compared civic projects there to raising a barn in Montana. “You need a hand to put a thatched roof up, and the whole community pitches in.”

In fact, Kathy was born into this spirit in the most literal way possible, when her parents first settled in Stevensville. “That’s how I came into the world. My folks were building a little ranch and the only thing done at the time was the garage. My brothers and sister had to run two miles down the road to the find the neighboring rancher and say, ‘My mother’s having a baby!’ The neighboring rancher cut my umbilical cord, and if that’s not being neighborly and pitching in...”

This extends to another quality Montanans and Rotumans share: “Most people don’t get too wrapped around the axle,” Kathy notes. “People are pretty light-hearted, and I find Montanans to be similar; we don’t get too bent out of shape over our differences. We’ll have a beer together and find common ground.”

Kathy Weber-Bates hiking Waterworks Hill Trail in Missoula with her daugher Isalei and son Kavika.

Kathy speaks about another benefit of becoming more involved in South Pacific culture as she’s taken part in the work of the Oceania Leadership Institute, which seeks to promote leadership skills derived from Polynesian cultures. “There are specific ways for mediating conflict that are cultural to us. The idea is to not hide away our Pasefika culture and assimilate, but rather to bring these values to your workplace; bring that heritage to your style of leadership.” These values help strengthen Kathy’s work back home, where she’s often collaborating with many people and organizations to accomplish ambitious goals. Each year now, a bit of that wisdom from a world away finds itself at work in a cow pasture somewhere in the middle of Montana—Kathy’s one of the core team members of the Red Ants Pants Music Festival in White Sulphur Springs in July.

Meanwhile, Kathy recently returned from a second trip to Rotuma where she and Jonathan captured more of the 360-degree immersive videos which are his specialty, and their purpose and passion shines through. Whether you’re a native-born Rotuman, of Rotuman ancestry, or just an interested third party in a very cold, rural part of the Big Sky, seeing footage of these places and hearing the music that’s made there speaks with quiet force. It’s the sound of generations of Rotumans, living and otherwise, softly speaking that this place still survives.

“Am I hearing the whispers of some of our ancestors as I go forward on this project along with my cousin?” Kathy reflects for a moment. “We both have remarked on a couple of occasions that this is what we were meant to do. And, we feel blessed and grateful to be able to contribute our small part to documenting and perpetuating our Indigenous island culture.”

Visit the the Rotuma Project at https://therotumaproject.com/

Tags: Missoula, Rotuma, culture and language