Home, Made

Imagine you’re an art major. Call it the early 1970s, and you and fellow students have spent a lively evening at the home of two of your favorite teachers, one of many informal gatherings where good conversation and laughter have been shared. The home is on the outskirts of town, and if the evening has run late, cubbyholes behind the snug living room’s built-in couches hold blankets and pillows for guests. One or two shaggy-haired undergrads clad in Levi’s and flannel shirts, snoozing within the cozy midcentury space, would have been quite a sight—especially since nearly every horizontal surface in the place contained wonderful ceramic art, much of it made by the students themselves.

Perched on a wooded hillside not far from the campus of Montana State University in Bozeman that funky, unassuming house still stands. Built in 1953, it was created as a home and studio for a pair of remarkable artists. But in the years following its completion, the house became much more than that—it might have been the de facto epicenter of the arts in Montana. And that’s due to its extraordinary inhabitants: Frances Senska and Jessie Wilber.

What’s perhaps most remarkable is that Senska didn’t attempt to build the entire structure singlehandedly; her work ethic around craft and utility meant figuring things out on your own, making things by hand as they were needed, and letting form be shaped by function as well as fashion.

Today the Senska-Wilber house remains a vital force in the arts due to its ongoing use as a home and studio by Shelburn Murray, Senska’s friend, caretaker and fellow ceramic artist. Shelburn inhabits the home with a light touch, leaving much in place just as Frances and Jessie left it. Indeed, watch Art All the Time, a KUSM documentary filmed there in the ’90s, and you’ll see the home as it was then—with much of the art and furnishings in the same spots they are today.

Sitting on one of those handy living room couches, I spend a Saturday afternoon with Shelburn, West Yellowstone poet Noelle Sullivan, ceramicist Stephanie Alexander and MSU School of Art Interim Director Josh DeWeese for a tour and discussion of Frances’ home and work. The inseparability of the house and its contents, in fact, is the result of its owner’s life and upbringing. Born to missionary parents in Cameroon, Africa in 1914, Frances Senska came of age learning to make whatever she needed: furniture, tools, cups and plates. Shelburn relates that Frances stitched almost all her own clothing along with the jewelry to go with the outfits, some of which she referred to as costumes. Preparing for the Senska family’s return to the States when Frances was still young, her father carefully selected the wood for the crates he nailed together to ship their possessions home; on their arrival in America, he disassembled those crates to build furniture still found in the home today.

The Senska clan’s do-it-yourself ethos quickly found its way into Frances’ work. She completed a B.A. and M.A. at the University of Iowa and began teaching painting and drawing at the state’s Grinnell College. But when World War II erupted, her job ended; the school decided the war effort needed a physicist more than an art teacher. So, Frances joined the Navy.

It was while stationed in San Francisco as a WAVE that Frances first discovered ceramics and following a series of classes and workshops (including with Bauhaus icon László Moholy-Nagy at the School of Design in Chicago), she found herself at Herrick Hall on the campus of what was then Montana State College. The college’s entire art program was a part of the home economics department and had its home in the Herrick basement, and ceramics and pottery were viewed at the time as a thrifty, practical, decorative craft. Frances didn’t necessarily disagree, but she also knew that it was as valid an art as any.

By way of example, Shelburn holds up a distinctive lidded jar, the size of a gallon milk jug, black with incised figurative designs, and cradles it to her chest. It’s what Frances called a Ya Ba Bo, an African-influenced vessel whose name translates as “it will be nine.” In Cameroon, the number nine was associated with luck and each Ya Ba Bo would be personalized with details of an individual’s life to reflect good fortune. Damaged, it had been conscripted for service as a cookie jar, a use Frances found as noble as anything else. And when Frances passed away on Christmas Day in 2009, the vessel took on one more useful role—holding her ashes before they were scattered on the property.

Building an art program at Montana State was a similar process of matching purpose to need. Cobbling together a studio, and students to fill it, meant resorting to unusual means.

Dan Clasby, a grad student studying with Frances, did more than work there. He’d discovered a sort of hidden nook in the Herrick Hall basement and took up residence in it, unbeknownst to anyone. Except Frances. She’d come by in the mornings and knock on its paneled door to get Dan started for the day. Another promising student was so eager to work and make ’round-the-clock use of the studio’s kiln that he took to slinking in and out of an unlocked window late at night. “Peter,” Frances remarked once she heard about it, “if you wanted to come in at night, I could have just given you a key.” The would-be cat burglar was Peter Voulkos, who’d go on to be one of the foremost ceramic artists of his generation.

As the program grew, so did its staff. Frances hired Josh DeWeese’s father Bob, and he and his wife, artist Gennie DeWeese, relocated from Iowa. When they arrived in Montana, Frances sent a couple of students over to unload the DeWeeses’ car—Voulkos and Rudy Autio, another future giant in the field.

Hauling furniture wasn’t the only manual labor Frances roped her students into. Josh recalls a long road trip to Lewistown, where Frances knew where to find a distinctive purple clay: in a roadcut exposed along an abandoned spur of the Milwaukee Road’s electric rail line. Just as fly-fisherman have been known to speak in whispers, jealously hoarding knowledge of the best riffles and pools, more than one potter has proven tight-lipped about a good source of clay. Not Frances. Employing an unrolled flume made of canvas, her students would heartily send loads of this “Kootenai clay” careering down the hillside; they’d bag it up and bundle it into the truck like crazed cattle rustlers. On that trip, Josh recalls, they overloaded fellow ceramicist Jim Barnaby’s truck; when they headed home it took them most of the night to get back to Bozeman, riding the axles all the way.

Frances gathered and molded and fired up her students in the same way she shaped her utilitarian, earth-tone pots. No fan of shiny finishes or porcelain daintiness, her work and her approach to the school were the same: functional, honest, straightforward.

The home she and Jessie made reflected this as well; Jessie’s shoji screens above the built-in couches are a simple and eloquent contribution to the whole, much as her prints drew on the spare sensibilities of Japanese woodcuts. Shelburn remarks that even the house’s location was a bold statement when it was built, saying people thought it was out “in the sticks” in those days. Bozeman’s rapacious growth has changed that; the house is surrounded by town, and the growing MSU campus is easily within view. Indeed, our chat is briefly interrupted by the dull boom of the stadium’s touchdown cannon when the Cats score against Idaho State.

Fortunately, the cannon is too faint to rattle the home’s contents, and that’s a good thing.

Pottery and art abound: pieces by Voulkos, Autio, the DeWeeses, and many other students and contemporaries join Frances and Jessie’s own work.

And in the time she’s owned the home, Shelburn has been steadily adding her own creative output to the collection, shaping all of it in the adjacent studio built in 1969. Like the house, it’s snug, useful and filled with things Frances made. Several hand-sewn smocks hang from the side of the large gas-fired kiln at the center of the room; your eyes widen with wonder as you realize their buttons are hand-made, too: tiny schools of seeds suspended in half-round domes of resin.

Shelburn turns on a tape deck and African rhythms fill the small, cinderblock-walled space. Frances preferred music with energy while she was throwing and kept a steady stream of new African and Asiatic music flowing to Montana courtesy of an ethnomusicologist friend in Portland.

Asked what kind of tunes she likes working to, Shelburn hits Play on her own cassette deck and the Bee Gees’ “Night Fever” thumps into the space, mixing with Frances’ rhythms. These mingled measures fit the vibe: multiple artistic visions and generations, melding through a common excitement for making great things.

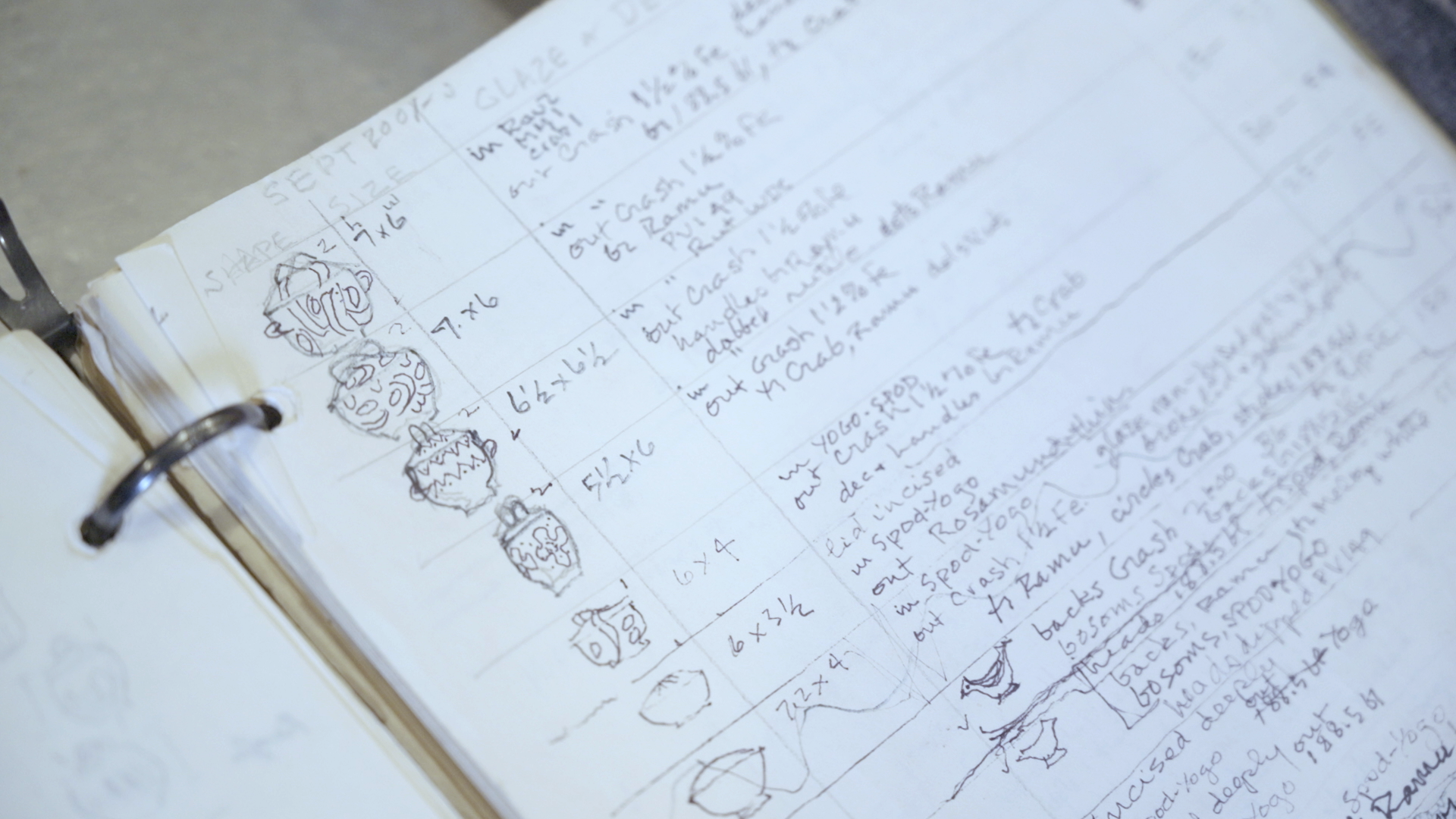

Coffee cans and jars line the walls, reliquaries for Frances’ glazes (home-brewed, of course), names labeled on tape: barium carbonate, Colemanite, ball clay. Shelburn’s works in progress litter the center of the space in a delightful profusion of ideas and forms. Hand-written notes dot walls and cabinet doors: Get out of your own way; You may admire my dust but please don’t write in it. On the worktable lie Frances’ astonishing notebooks, in which she recorded every item she ever made—clay type, shape, firing method, date, to whom it was sold and for how much—each with a postage-stamp size sketch. Shelburn has adopted this method as her own, and the notebooks continue to fill.

Tucked into a far corner is perhaps the most significant artifact in the space. It’s Frances’ original kiln, a layered wedding cake of foil-lined bricks arranged in stacked octagons, each with its own heating element and power cord running to the wall.

The rings can be heated individually, employing an arcane blend of 110 and 220 current as needed. Of course, it was her own design and construction; one can only guess how much of her work has passed through this beating hearth and into the world where it’s loved and studied to this day. Process and result, always the fusion of Frances Senska’s belief in doing it yourself, doing it by hand and doing it right. Ever thrifty, each time she’d load the kiln Frances would note the empty spaces between pots and then sculpt corresponding figures to fit inside them. Many of these are her birds, tapered quail- or Hungarian partridge-shaped figures propped up with plucky little feet. As with everything in her life, Frances had a knack for seeing little voids and filling them with good things. So keep your eyes peeled—if you’re lucky, you might spot one her birds at an antique store in town, where they’ve sometimes been known to alight.

I peer in for a last look at the kiln, waiting to be filled and fired once more, and realize I’ve miscounted. Each of its rings isn’t an octagon at all; there’s one more brick in every course, each of which has orbited and warmed and transformed the work of all those years, baking in her love and thought and care.

Not eight bricks at all. Ya Ba Bo. It will be nine.

Read Noelle Sullivan's poem, "Worldmaking," a response to Frances Senska's home and work, here.

Tags: pottery, Bozeman, ceramics, Montana State University, School of Art, Frances Senska, Jessie Wilber and Montana Art News