A Closer Look

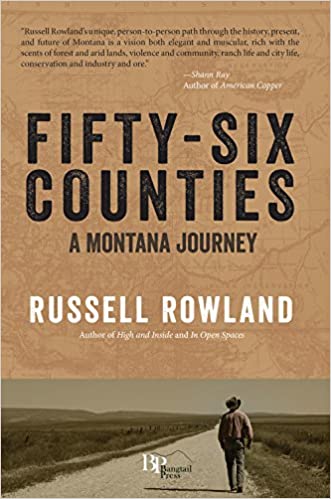

About seven years ago, when I began my journey for what would become the book Fifty-Six Counties, I made a couple of conscious decisions about how I was going to approach this project. My objective for this book was to get a spontaneous view of what is happening in Montana today, so except for a handful of discussions I scheduled in advance, most of the interviews I did were on the spot. I didn’t want a whitewashed, Chamber of Commerce version of what’s happening in each county.

The second decision I made was to limit the time I spent doing research and writing this book because I knew it was the kind of project that could last for years, and that the more time I spent getting bogged down in research, the further I would take myself from that spontaneous reaction to each place I visited. I wanted my own take on this journey to be as fresh as possible.

There were a couple of natural disadvantages to this approach, the first being that my experience with each county depended in large part on who I happened to encounter. And the second was that the limited time on research meant that I missed some important details. I knew this would be an issue with some readers, so when the book came out, I braced myself for the inevitable criticism.

And it came. But the most pleasant surprise, especially in this age of unadulterated vitriol in comments sections all over the internet, is that every single email I received that was critical of Fifty-Six Counties, was thoughtful, respectful and often filled with excellent information to back up their arguments. Just last week, I got an email from a reader in Ravalli County who was very unhappy with the way I portrayed Marcus Daly, who built a huge mansion in the Bitterroot Valley not long before he died. I was admittedly hard on Mr. Daly in my book, mostly pointing out that after paying several experts to dispute the idea that the toxic smoke emitted from the smelter Daly built in Anaconda was harmful to the area, he moved his own family across the Rockies to a safer place.

My reader friend did not dispute the criticism I offered toward Mr. Daly’s business practices, but what he found upsetting was the fact that I overlooked so much good that Mr. Daly did. He gave me a long list of evidence, including the fact that Daly plotted the layout of Hamilton to give the homeowners bigger lots than they have in Butte or Anaconda, or even Missoula. He also pointed out that the Daly family donated much of their land to the city, for churches in particular.

So one could argue that the fact that he had so much land to begin with was largely due to his questionable business practices, especially when it came to paying his workers a living wage. But the point is pretty simple. This man thought it was important that I tell a more complete story, and I couldn’t argue with that. So I wrote and thanked him for his input, admitting that I should have taken a wider view of the situation.

My favorite email by far came to me about a year ago from a young woman in Lewistown. Emily Standley is an extension agent for both Fergus and Petroleum Counties, and she was very disappointed in my depiction of Petroleum County in particular. And she had every right to be. Things had not gone well on the day I visited Winnett, which is the smallest county seat in Montana. I started that day’s journey by stopping in at the county courthouse, where someone told me that my best bet for an interview was a man named Jack Barisich. Jack was the man who carried the mail in Winnett, but he was also considered by anyone I asked to be the town historian, so I made a valiant effort to find him that day, going first to the post office and then to his home when the guy behind the counter told me that he had gone to lunch and would probably go home from there for the day. After going to the wrong house, and having a very nice woman point out the correct address, I found nobody home and after waiting for about an hour, I decided to move on. I took an admittedly rushed view of this tiny town, and wrote about Winnett being one more dying community.

Emily Standley explained in her email that Winnett has an organization called ACES (Agricultural Cultural Enhancement and Sustainability) that was doing incredible work to make the community more viable and attractive to young people who want to return to the county. She made several other valid points (and also, as with most of the people who contacted me, pointed out the parts she liked about the book), so I wrote her back and thanked her.

About two years later, when I started doing the radio show based on Fifty-Six Counties, I thought of Emily, and contacted her to ask whether she would be willing to do an interview, and also whether she would hook me up with a couple of people from Winnett for an episode about Petroleum County.

So in the second week of June 2020, just before the state shut down, I walked into the County Courthouse of Petroleum County six years after I visited it the first time, and met Emily Standley in person. She had invited two friends of hers, Brenda Brady and Jay King, two of the board members for ACES, both younger people who had returned to the family ranch after leaving for a time. And for the next hour, we talked about all of the exciting things that are happening in Petroleum County, including a program ACES set up to donate beef to the school. After a study about how much they were spending on food for the lunch program at the school, and realizing that four head of beef would supply enough meat for an entire school year, they asked local ranchers whether they’d be willing to donate a head of beef. Before they knew it, they had enough beef donated to provide for the next six years.

They also talked about discussing preliminary plans to build a community center, in a town where the only building that would hold more than 100 people was the school gymnasium. Once the word got out, a native of Winnett named Larry Carroll, who had done very well for himself as a petroleum engineer, donated five million dollars, not only enough to plan and build the center, but also to set aside an endowment to finance the maintenance of the building for years to come once it’s built.

This episode of Fifty-Six Counties, remains one of my favorites, because it was such a surprise, and because this conversation turned out to provide a stark contrast to my first visit to Winnett. That hour reminded me of something I wrote about in the book, a piece of advice I threw out to the world but apparently didn’t always apply myself. I mention several times in Fifty-Six Counties, that most of Montana requires “a closer look” to appreciate what you’re looking at. If you jump to conclusions about any of these small, dusty towns, you’re bound to miss something interesting, something surprising, and sometimes even something remarkable.

But there’s still a tendency, even for a native Montanan like me, to make assumptions about the small towns in Montana from a first impression, shaded by lingering stereotypes. When I was doing my tour of the state, I pulled into Plentywood, which is in the far northeast corner of the state. My usual routine when I pulled into every town was to drive around and look for interesting places, businesses or organizations that might lead to an interesting interview or story. So I started driving around Plentywood on a sunny summer afternoon, and I soon noticed a big black pickup behind me. At first I thought I might be paranoid, but each time I turned, he took the same turn, and eventually I had to admit that he was following me.

I wasn’t scared, but I did wonder what transgression I had committed, so I eventually decided I better just pull over and give him a chance to explain. So I pulled into a parking lot and rolled down my window. Sure enough, he pulled in next to me, facing the other direction, and rolled down his own window. “Just wanted to let you know that your right rear tire is low,” he explained.

Tags: Montana Art News, Russell Rowland, 56 Counties, Travel, book and Literature